THE 2023-2024 WINTER FORECAST: A RETURN TO FORM?

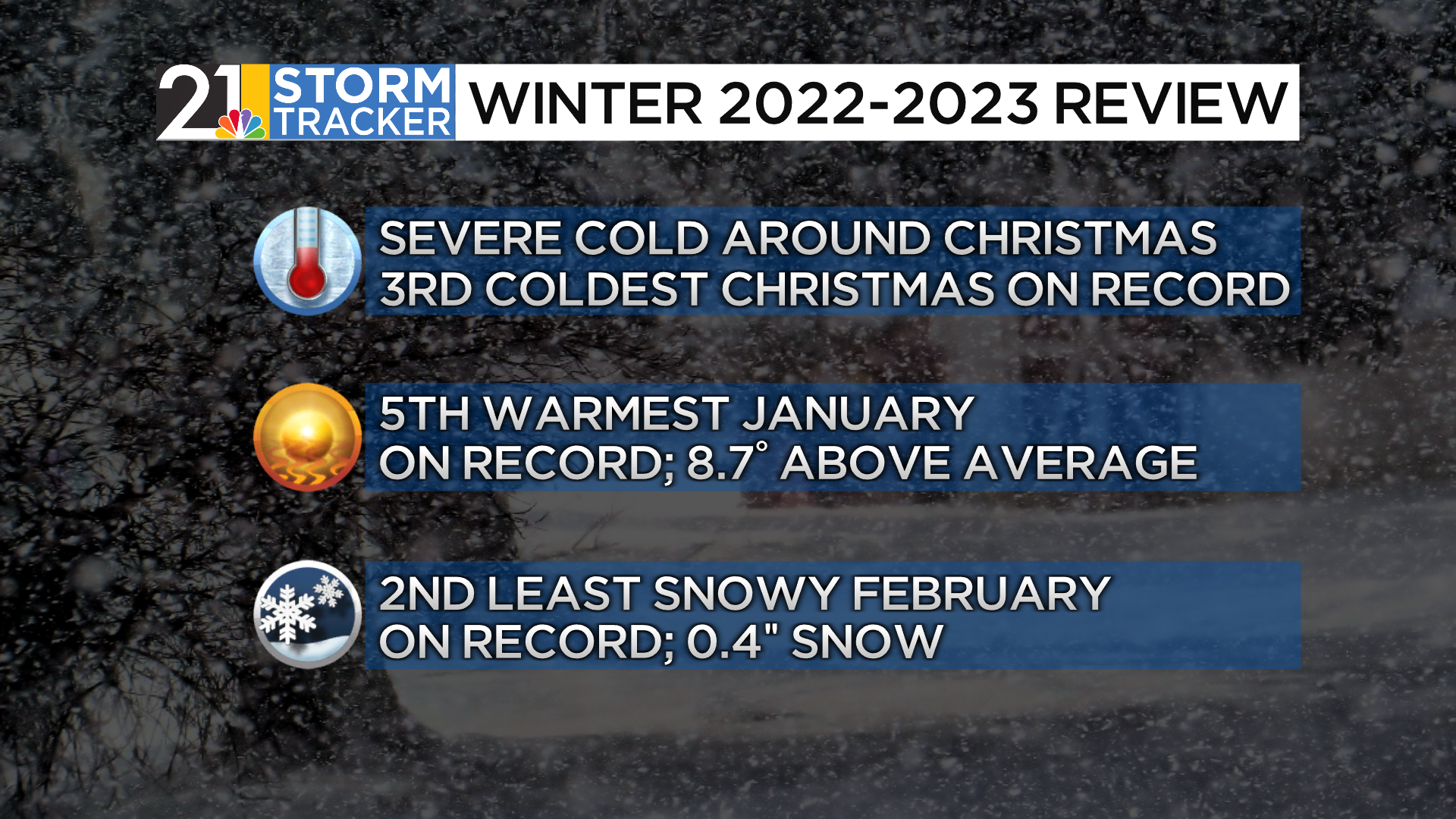

FIRST, A QUICK REVIEW OF LAST WINTER

The forecast stunk. Let’s just get that out of the way up front. There are meteorological reasons why the 2022-2023 forecast went sideways for me and well, nearly everyone else. You can read a brief summary here:

Forecasts busts like last year are going to happen sometimes when we are trying to predict weather trends on a seasonal scale. It’s just the nature of the beast! But, lessons are learned and we move on to the next challenge.

Just a reminder about the time period we refer to in these winter outlooks. We define “winter” as “meteorological winter”, or December-February. When it comes to snow, we are talking first flake to last flake (usually October-April). That said, here’s last year’s numbers…which were pretty crazy.

22.8” is a shockingly low number for the Youngstown-Warren Airport in Trumbull County. There is a fair amount of our television viewing area that had single digits/lower teens snow totals for the season.

Average snowfall for our region:

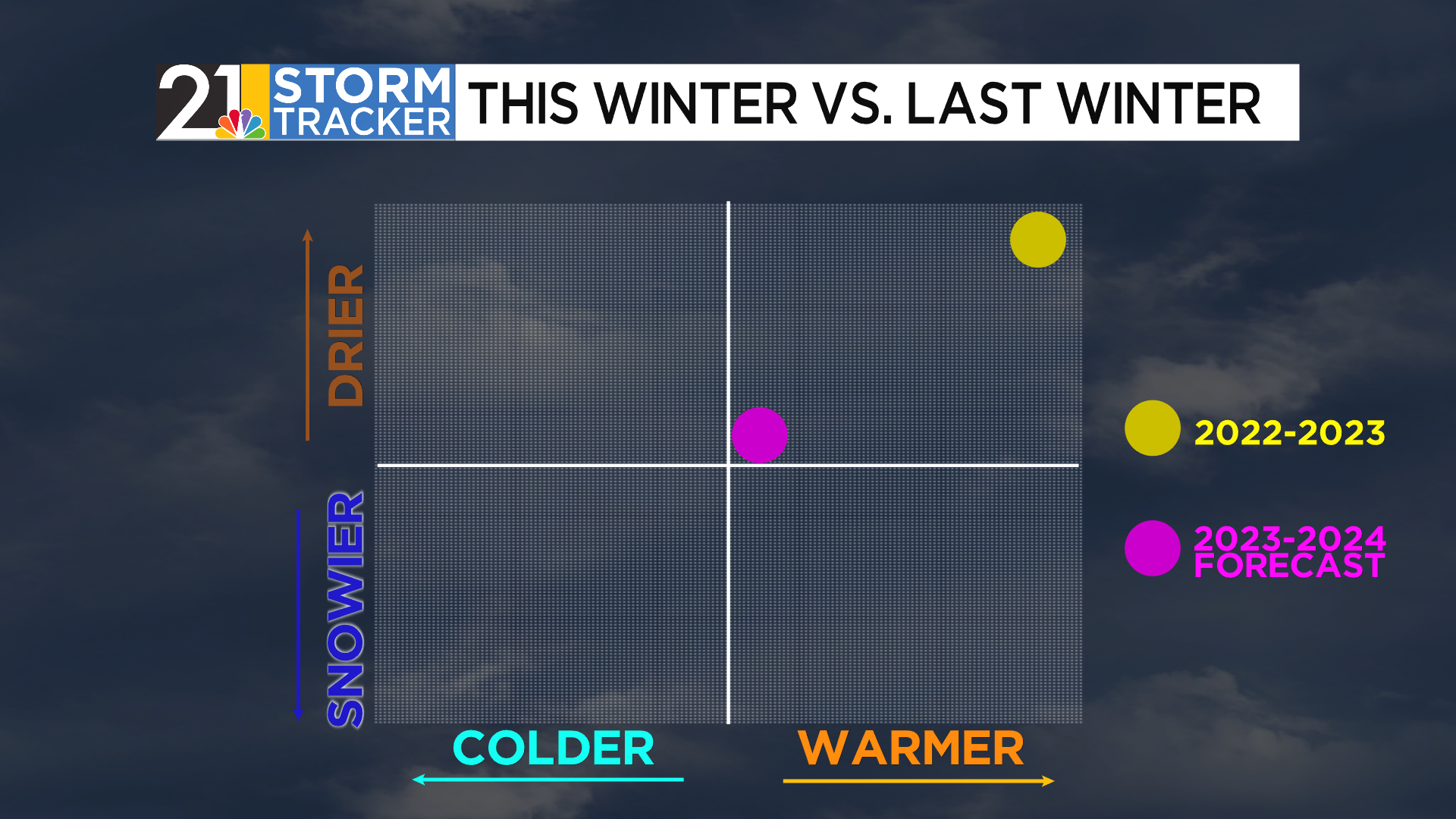

2022-2023 was a remarkably snow-free winter and also very mild…and mild winters have been the rule since 2015-2016, which was a winter featuring a “super” El Nino. The winter of 2017-2018 was just about average, but every other winter since 2015 has been on the mild side.

HOW DO WE MAKE THESE FORECASTS?

A seasonal forecast is much different than the standard 7-day forecast you see us do on TV and online every day. A seasonal forecast is all about forecasting temperatures and precipitation compared to average, general trends, etc. Despite what you may find in the Farmer’s Almanac, it’s not possible to say there will be a snowstorm on February 11th months in advance.

To formulate a long-term outlook, we rely on “analogs”, past years that had a lot of similarities to the state of the atmosphere and oceans this year heading into winter. We use long-range computer models, carefully, and with a lot of caveats and grains of salt. Lastly, experience and intuition are important. I’ve learned a LOT over the last several years and tried to catalog all the successes and failures.

This is hard business. Seasonal forecasting can also be a high-stakes endeavor. There are meteorologists in the private sector who rarely, or never, worry about what’s going to happen 3 days from now and instead focus on long-range outlooks. Utility companies, energy traders, etc. rely on these forecasts to make decisions in which LOTS of money is on the line.

FACTORS IN THIS YEAR’S FORECAST

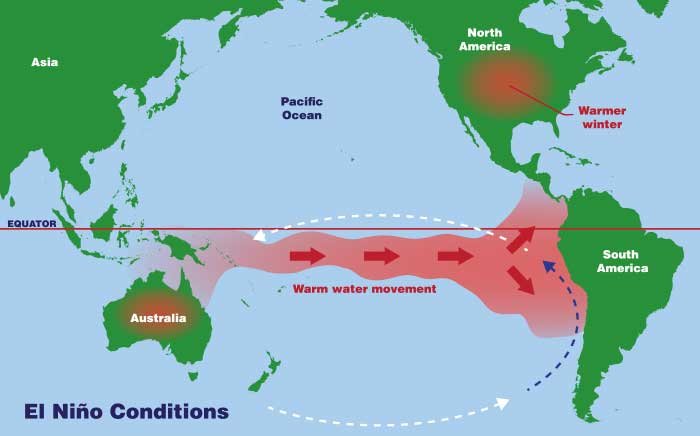

The winter 2023-2024 forecast is a somewhat different beast than the last few years. Why? Well a few reasons, but the main one is the presence of EL NINO in the Pacific Ocean. This is the first stout El Nino we have had since 2015-2016 and comes on the heals of the opposite phase, LA NINA, for the last few years.

Simply put, El Nino is the warming of the waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. La Nino is the opposite (cooling instead of warming).

Ok, well, so what? What does warm water in the Pacific have to do with how much snow we will see this winter?

The ocean and atmosphere play together in the same sandbox. The ocean can influence the behavior of the atmosphere and vice versa. A warm tongue of water in the Pacific can alter atmospheric patterns, storm tracks, etc. So, El Nino is important, but it’s not at all cut and dry. We have to factor in:

1) The strength of El Nino. This year’s El Nino is strong and still strengthening, but as outlined below, it may not “behave” quite like a strong El Nino.

2) The location of the warmest waters in the El Nino zone. If the warmest waters are near South America, that favors a warm winter in the eastern US. If it is a “central based” Nino, that tends to favor a colder outcome for us. This year has been east-based so far, but may eventually become more “basin-wide” or a hybrid of central and east-based.

3) How much does El Nino “stand out” from the rest of the world’s oceans this time? Is this “zone” MUCH warmer than the surrounding waters, or not so much?

OTHER OCEANIC FACTORS

The Alphabet Soup on the image above shows the other major oceanic oscillations that are important this year. We won’t go too far into the deep end here, but a quick primer on what this stuff is and why it’s important:

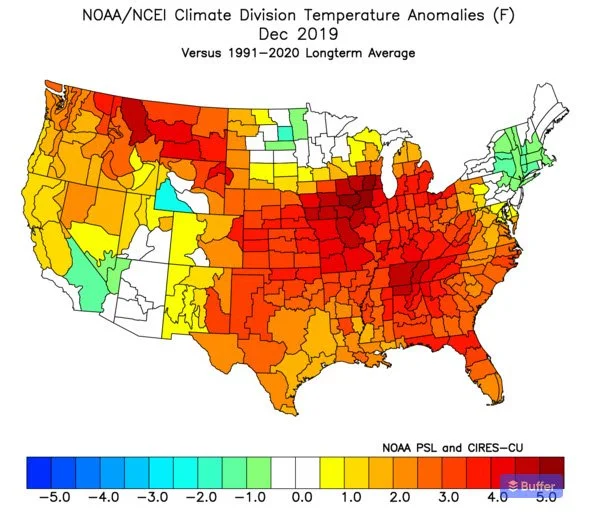

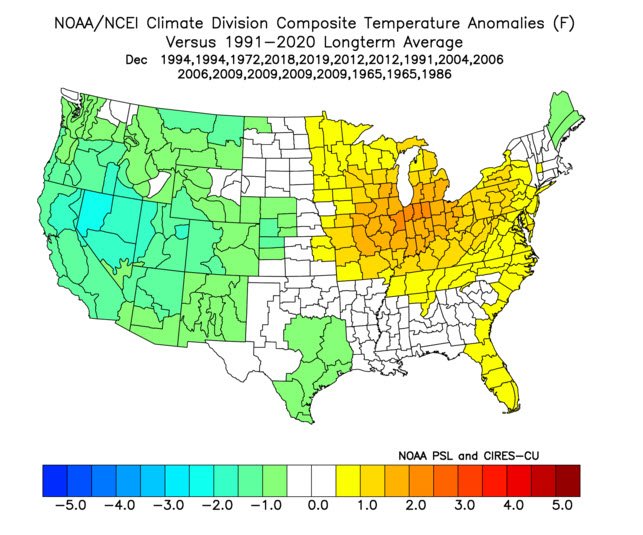

1) “+IOD” is the positive phase of the “Indian Ocean Dipole”. This basically means that there is cool water in the eastern Indian Ocean. This has big implications for Australia (bad drought) but it can also affect weather patterns over the Pacific Ocean enough that it’s important for the U.S., particularly when it’s as strong as it is now. A very positive IOD greatly increases the odds of a mild start to winter in much of the US. The last time we had a strong +IOD was in 2019 (although there was no El Nino accompanying it, which is pretty unusual) and December looked like this:

2) The “-PDO” is in the negative phase of the Pacific-Decadal Oscillation. This is marked by a ring of relatively cool water in the eastern Pacific and warmer waters in the west/central Pacific. The presence of a -PDO, particularly a strong one like we have had recently, is rather usual during El Nino and is likely a “hangover” from 3 straight years of La Nina conditions.

3) The “+AMO” is the positive phase of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. This signifies the presence of very warm waters in much of the Atlantic Basin.

WEIRD EL NINO?

This season’s forecast is largely based on the premise that, while we have a pretty strong El Nino, it’s overall influence on the atmosphere may be neutered somewhat. Why?

1) The strong -PDO

2) The world’s oceans, as a whole, are incredibly warm right now. This makes the El Nino STAND OUT less. It’s like El Nino is the big, loud guy at the party who usually dominates things, but this time the party is super crowded and the music is unusually loud. He just can’t stand out as much.

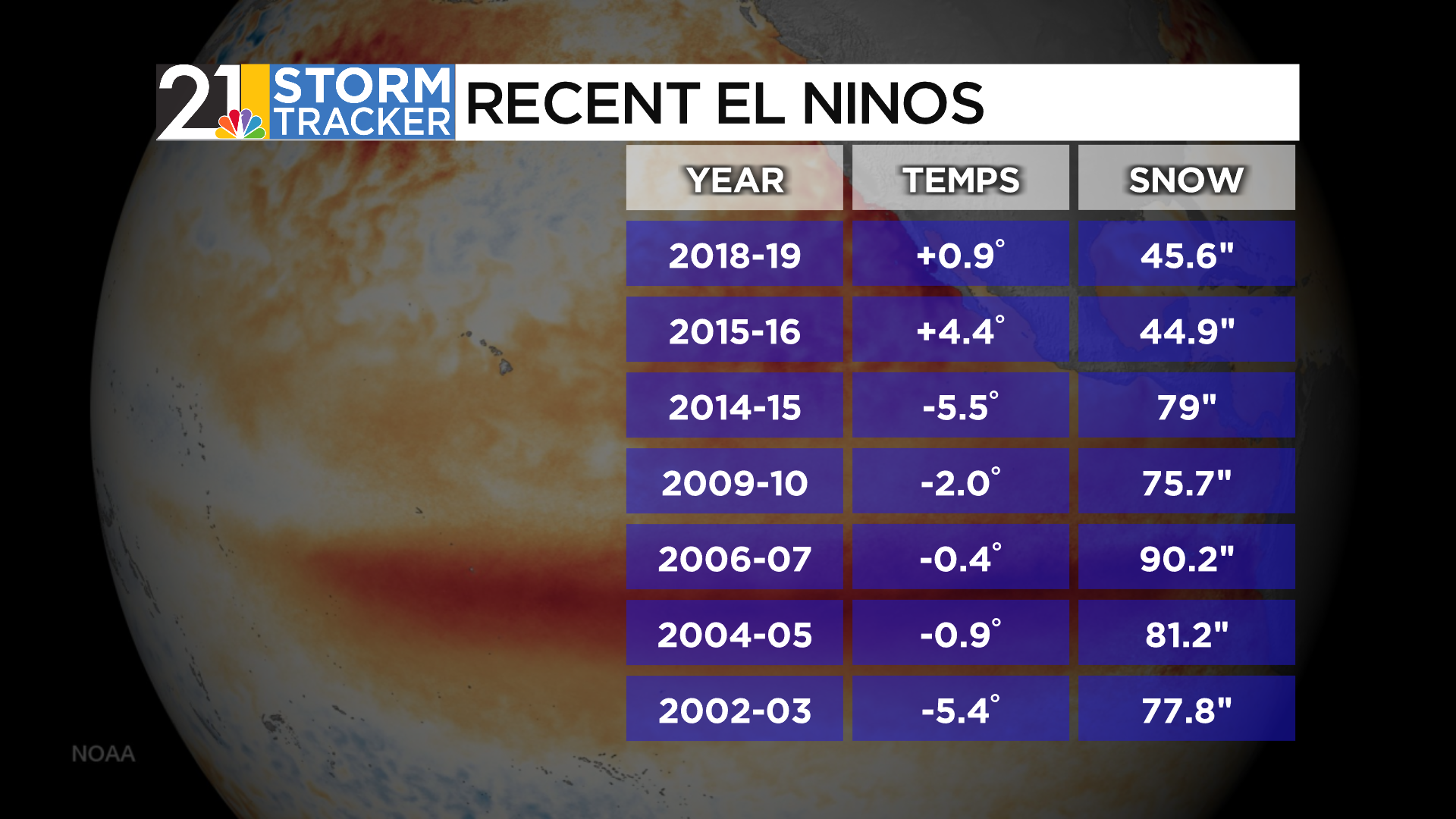

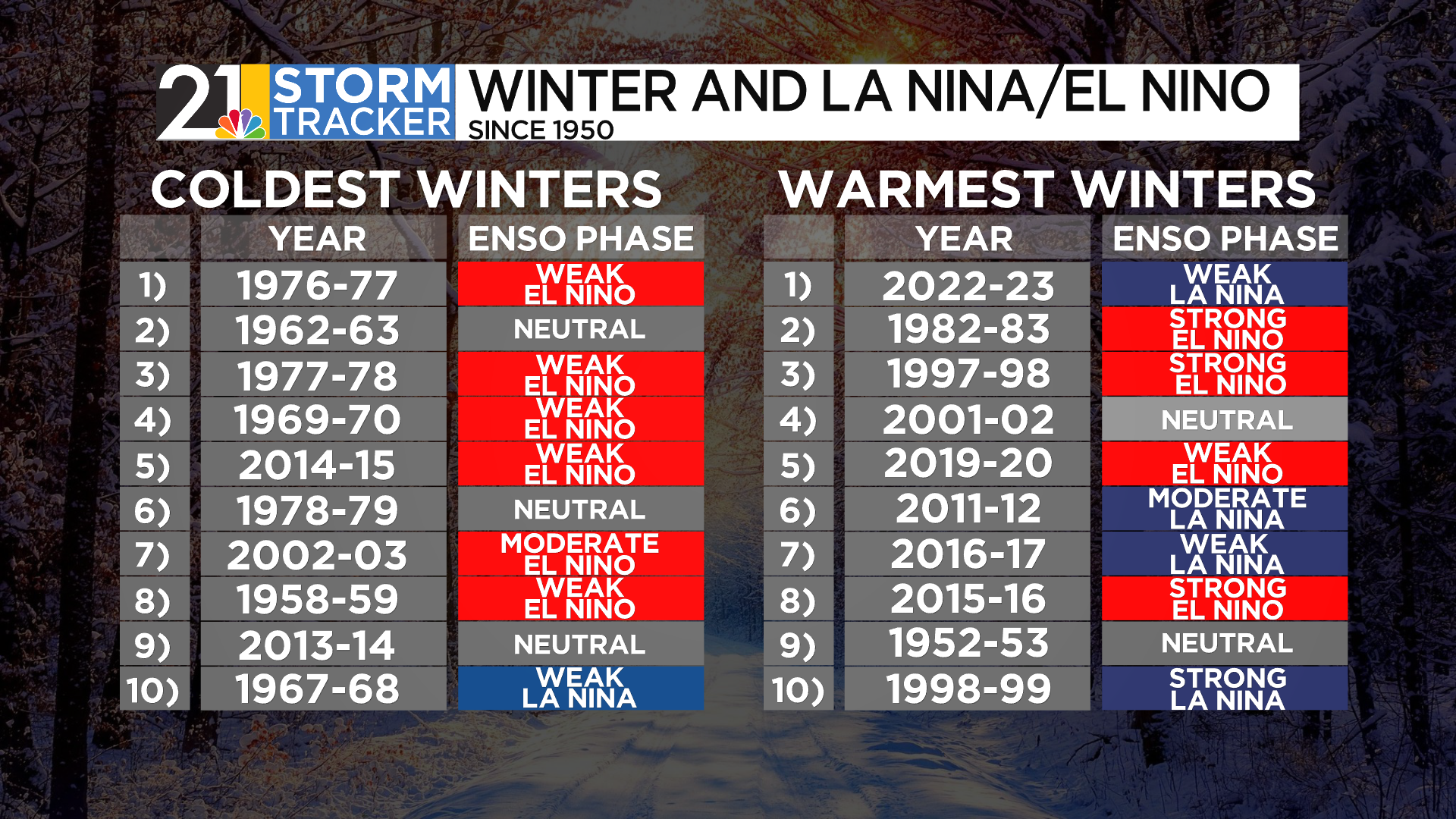

EL NINO AND WINTER WEATHER HISTORY IN OUR AREA

Keeping in mind all the things discussed above, what have our winters been like during recent El Nino episodes? On balance, fairly cold and snowy!

But here’s where I jump in and remind everyone that the STRENGTH of El Nino is important. On the above list, only 2015-2016 was strong…and you can see what a different outcome we had. Want cold and snow? You want a winter with a weak to moderate El Nino:

ATMOSPHERIC FACTORS

So far, we have focused on what’s going on in the oceans. What non-oceanic factors are important this year?

Potentially favorable setup for a weakened polar vortex

-Perhaps counterintuitively, a weakened polar vortex can increase the frequency in which bitterly cold air descends southward into the mid-latitudes (where we are!). A strong vortex usually stays put over the North Pole and keeps the really cold stuff locked up there. So why might this winter bring higher odds of a weakened vortex? Bear with me, this gets pretty nerdy:

-Research has shown that when a belt of wind high in the stratosphere are blowing in certain direction (nerds: it’s the negative phase of the Quasi Biennial Oscillation), especially during a part of the 11-year solar cycle in which sunspot activity is increasing (see image), a weakened polar vortex can occur more frequently.

Hunga Tonga volcano?

-So I just outlined an argument for a weaker polar vortex at times this winter. There’s also an argument to be made for a STRONGER vortex. Why? An underwater volcano eruption nearly 2 years ago. Say what?

-Hunga Tonga erupted in the western Pacific in January 2022. Since it was an under water event, by and large, it shot much more water vapor than sulfur into the air. In fact, the amount of water…and the height of the water was INCREDIBLE. We are talking way up into the stratosphere. Now that water vapor, initially swirling over the southern hemisphere, is working through the northern hemisphere. It’s been speculated that the presence of this abnormal amount of water vapor will cool the stratosphere and lead to a STONGER polar vortex in the northern hemisphere winter. But there is LOW CONFIDENCE in this idea. It’ll be very interesting to see what happened in a few months. This image shows the concentration of water vapor at high altitudes over the arctic region:

OK, so let’s quickly summarize before we get to the forecast:

1) We have a strong El Nino this winter, although it’s impacts on weather patterns may resemble a weaker El Nino event.

2) Odds may favor a weaker polar vortex, but confidence is on the lower end as of this writing.

THE ANALOGS

Based on many of the factors listed above, here’s my list of top “analogs” for this season. Keep in mind, there is no “perfect” analog. History never repeats itself exactly. 2009-2010 looks like a very good analog this year and it was a rather cold and snowy winter here. Does that mean this year will be another 2009-2010? Not at all. But of course it’s possible that the winter will be more LIKE that season than some of the warmest and least snowy analogs.

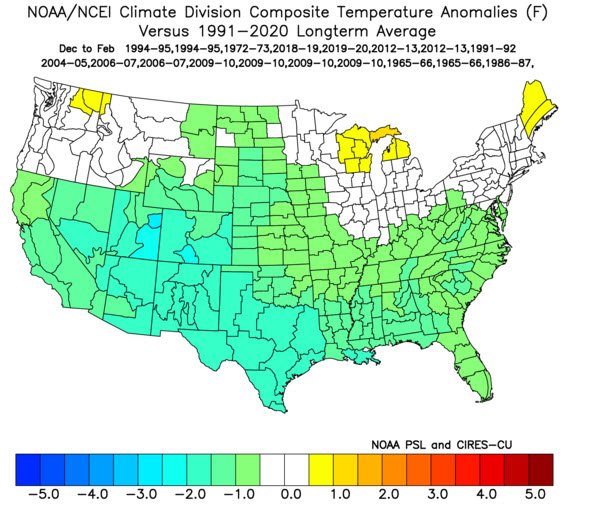

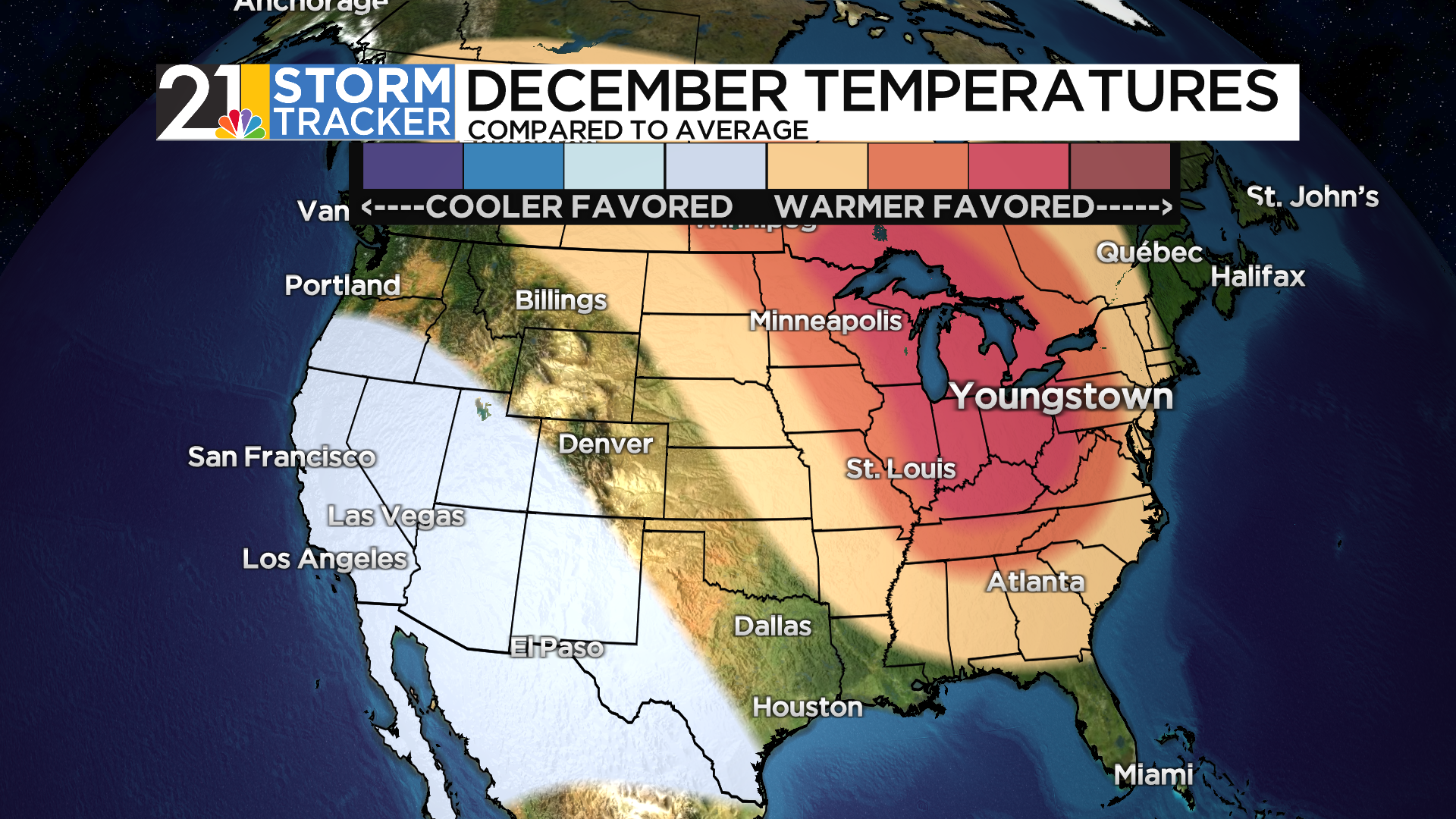

More weight was put on the analogs that seem to match this year’s conditions the best. A resulting national map looks like this for December-February temperatures:

Precipitation:

here are two very common themes among those analog years:

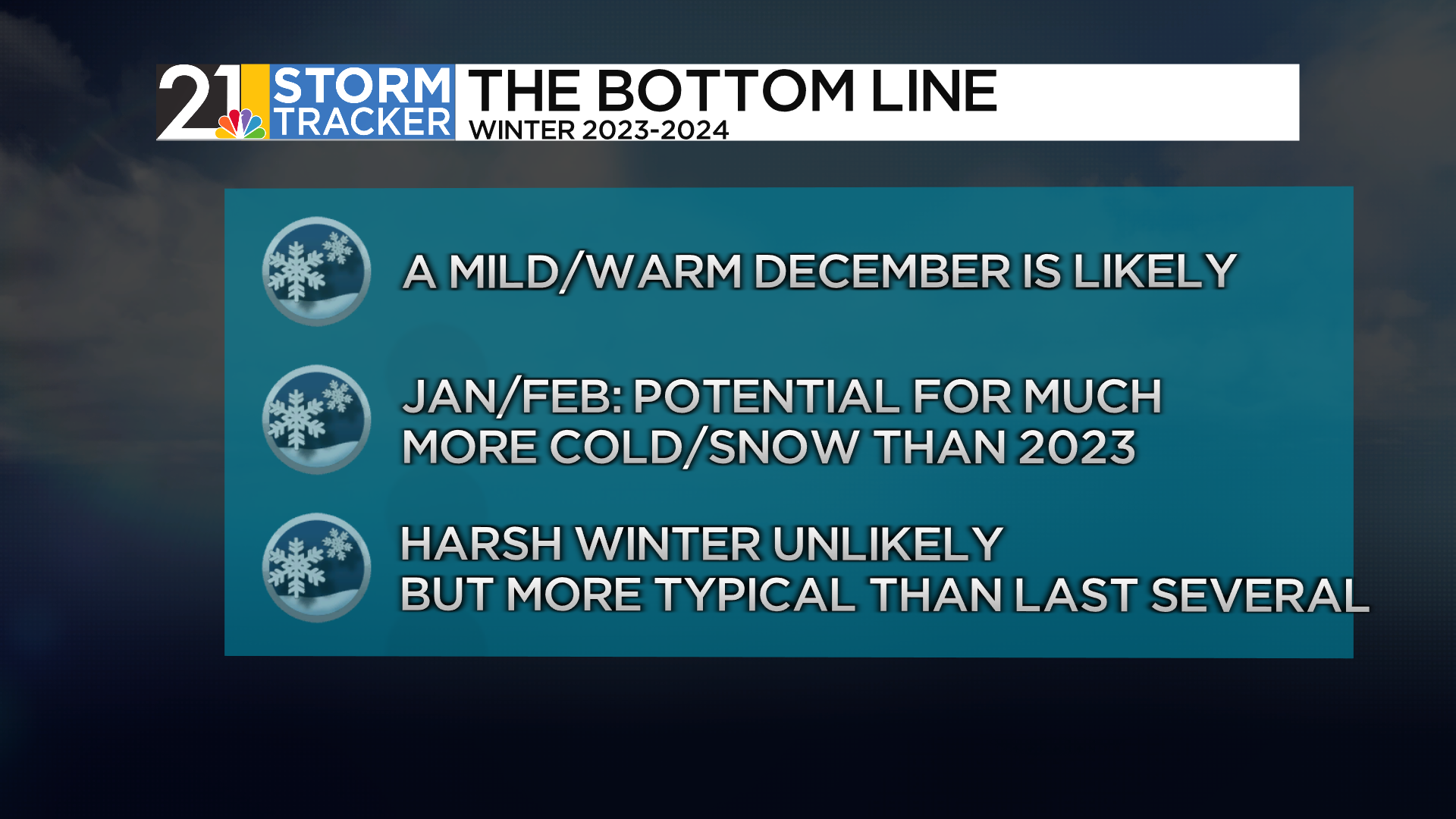

1) A mild/warm December

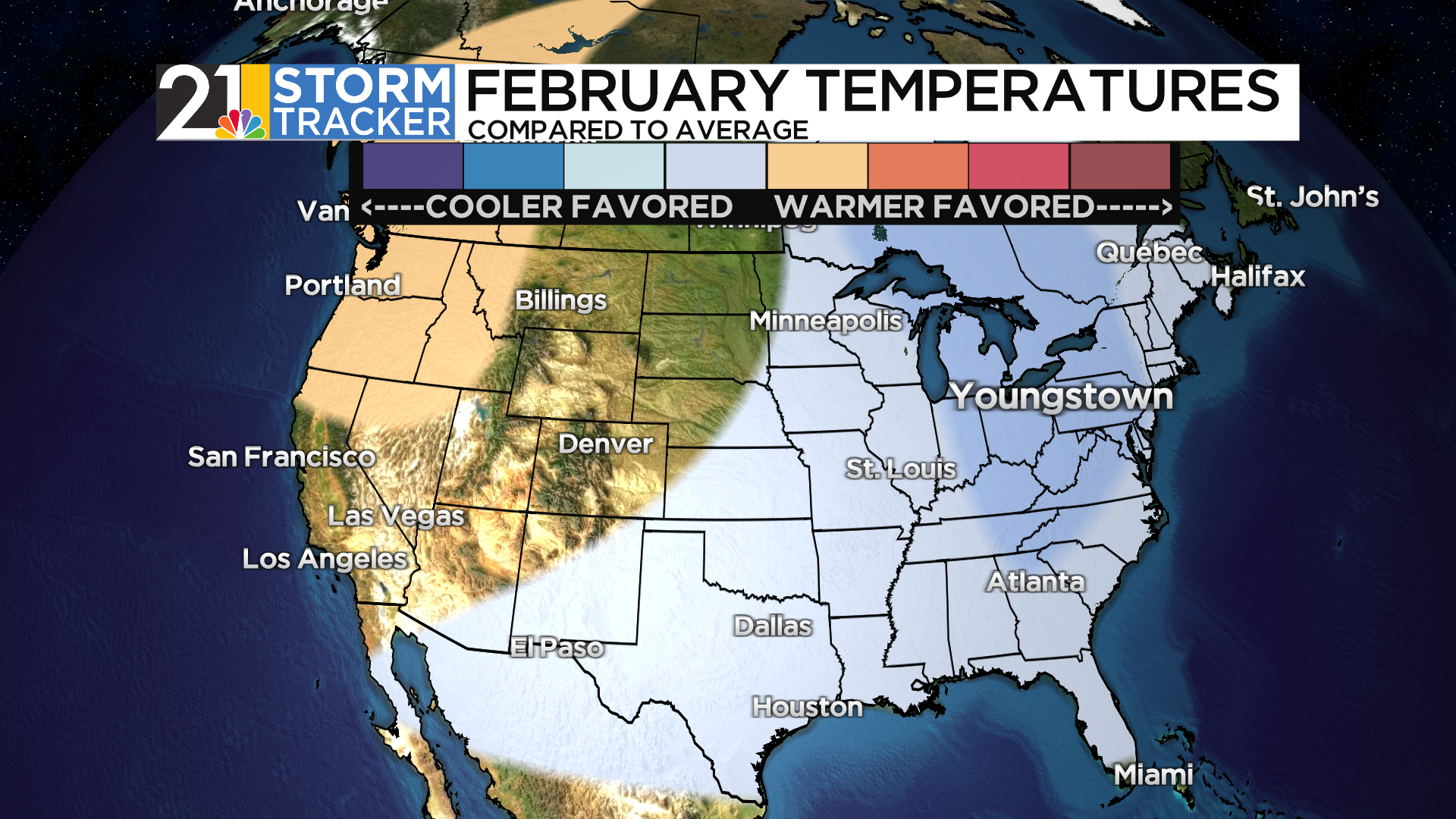

A cold February

Among the analogs, January is more of a mixed bag…some mild, some cold.

COMPUTER MODELS

There’s far too many seasonal computer models to show in this post, but I’ll show the most recent Canadian and European season guidance (temperatures):

Some differences, but some overall similarities: a warm winter for Canada, cooler in the southern US. Pretty typical of El Nino overall. Much of the modeling does agree with the analog composite idea of a mild December and cold February in the East, increasing our confidence that that is the correct idea.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

The overall idea I have for this winter is that it will almost be like 2 separate seasons. December may be, at least, partially, just “extended October/November”. It’s possible that “flavor” will continue into part of January. But I am bullish on the back half of winter being much colder and stormier that last year (that won’t be asking much) and many of our recent winters.

WHAT CAN GO WRONG?

Lots. As stated above, this is hard and complicated!

-The water vapor high in the atmosphere keeps the polar vortex very strong, limiting chances for true cold later in winter.

-Climate change/very warm global oceans conspire to “ruin” every “borderline” situation. In other words, storm tracks that used to give us snow more often instead produce rain/wintry mixes more often.

-The strong El Nino is neutered by the overall Pacific “base state” (La Nina hangover) so much that the winter reverts to a La Nina-flavor….limiting chances for a big back half of the season in the cold/snow department.

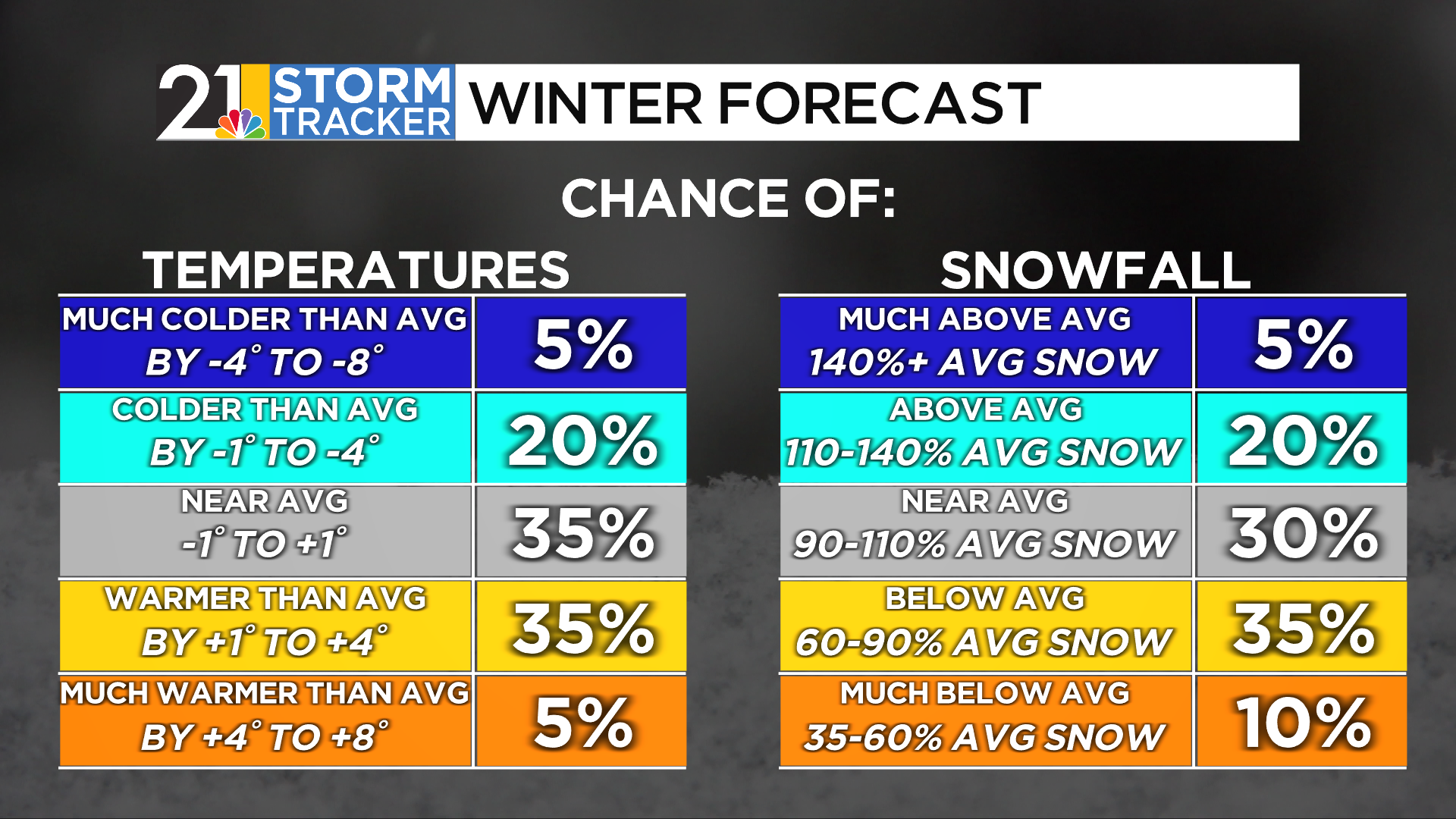

All that said, let’s show our cards.

The call is for the winter, as a whole, to be near average to perhaps slightly above average temperature wise. But with the caveat that December may end up quite a bit warmer than average and February quite a bit colder than average. Snow is tricky. Even a cold back half of the season does not guarantee a lot of snow. It can be just cold and dry. Given the likelihood of a balmy December, I lean toward the season being below average…but not by a big margin and, compared to last year it will SEEM snowy.

National map and monthly breakdowns:

Compared to last year:

The “Bottom Line”:

Look for an update to the forecast in about a month, in early December. Thanks for reading!